- Home

- Anthony Holden

He Played for His Wife and Other Stories Page 2

He Played for His Wife and Other Stories Read online

Page 2

‘Outside . . . gotta talk.’

Back at the table, I threw both arms around the chips and scooped them, messy and unstacked. ‘Fag break,’ I blurted, and darted up the stairs.

From the doorway I squinted into the darkness, panicking. Then I spotted that long, straight back. He was across the road. As I reached him Billy turned to face me.

‘What?’

‘Listen. Stay with me tonight, just for this game. I can get the lot.’

‘Why should I? I’ve paid you off, it’s over.’

‘Come on, Billy, what’s it to you? What about interest, and the headaches? I’ve had to work for the money. You still owe me.’

Billy’s eyes narrowed.

‘I don’t know,’ he said flatly. ‘A deal’s a deal, but . . . I wanna be fair.’

‘Fair, that’s it, Billy Boy. I only want what’s right. I know you’ll . . .’

He raised a hand to cut me off.

‘I tell you what. It’s a big game and you’ve got almost thirty grand in front of you. We’ll carry on until we find one big hand for you to get it in with. One big hand, to the river, against one player, then we’re done. But it’ll have to be very soon. OK?’

As I walked back in it looked like the game was breaking up.

‘Oh, here he is,’ laughed Tony. ‘Don’t tell me, you’ve had an urgent phone call from your girlfriend, she’s gotta have you now.’

‘What? No. It was your missus, Tony, and she can wait. I’m playing on.’

‘Well,’ he says. ‘Good for you, you’re what? Twenty up? I was sure you were gonna hit ’n’ run. Here . . .’ He tossed Shilling a hundred-pound chip. ‘You win, Nev, he wants to play on.’

‘Well, I’m done,’ says Shilling. Which had to mean Papa had somewhere else to be. Gary was getting up too.

‘You’re not going are you, Tony?’ I hoped I sounded calm.

‘What’s it to you? You haven’t played a hand against me all night. You never do.’

It was true, Tony was a scary man and a scarier player. If he smelled weakness he would put you to the test, again and again. His style didn’t suit me and I always stayed out of his way. But this was different. One hand. One big hand. There were five of us, and Tony had more in front of him than the rest put together.

‘How much are you playing?’ I asked. We both knew that he had played his initial twenty-five grand up to £93,400. He scanned his stack for an instant.

‘Ninety? Ninety odd?’ Like he was guessing the weight of a pig. ‘Why?’

‘I want to cover you.’

‘Well, pull up then. This I’ve gotta see.’

Everyone there knew that me and Tony had history, but knew what I thought about money too, what kind of a player I was, and near enough how much I was worth. No one could believe what they were hearing, no one except Billy. He knew what I was up to, I could see it in that sad old handsome face, and he knew I was pushing my luck. But then, like he’d said himself, a deal is a deal and I was gonna get my one hand. My one big, fuck-off, massive hand.

‘Don’t bother going to the cage,’ says Tony, reaching for his inside pocket. ‘Can you write me a cheque if you need to?’

I nodded.

He tossed three 25K plaques across at me like he was feeding the ducks in the park.

For a couple of rounds it was raise/fold, raise/fold. The other three, timid townsfolk at a gunfight, were still getting cards, but were no longer really in the game. They were composing tomorrow’s story and watching to see which of us would draw first.

I was in the blinds with a pair of sixes and Billy, permanently crouched now by Tony’s side – eyes level with the felt – called out the cards to me as he squeezed them up between his thumbs.

‘Eight of hearts . . . seven of hearts.’

Tony was on the button. I knew the raise was coming. He threw in six hundred pounds without a word. The action was on me and I made it eighteen hundred, regretting it even as I did it. We were playing deep and normally I’d just call and peel off a flop, but this was in no way normal. Yes, I was playing a man whose cards were face up, but I was playing Billy too. If Tony folded now we could play another hand, but if it went to the river it had to be big. I should build the pot now.

Pot building wasn’t gonna be a problem. Tony raised again, to five grand. I looked over at Billy and he understood my silent question. ‘Yes,’ he said. ‘I told you right. He’s got the seven-eight of hearts.’ So, Tony smelled weakness and he was putting the pressure on. This is what he does, why he’s so hard to play. I could have raised again, made it fifteen or even twenty to go. That should end it there and then. Against most players it would. But Tony had decided I was weak and I had no guarantee that he wouldn’t just push back at me for the whole lot. Then I’d be forced to just flip a coin for two hundred grand. No, I had to call the five thousand and hope he missed. The dealer spread the three flop cards in the centre of the felt: ace of hearts, king of hearts, two of clubs. Good bluffing cards for him, and a possible flush. I checked, and he bet the size of the pot.

Ten thousand pounds.

I hated this. I was still ahead with a pair of sixes but he would win with any heart and – though he didn’t know it – a seven or eight as well. I’d have to call and hope he missed the turn. For a man who knew all the cards, I’d never felt less in control. But the turn was OK: king of spades. I was still ahead.

I’ve thought about this a million times and I know what I should have done. Move all in and pick up the thirty grand. How could he call? But what was it Billy had said? One pot to the river, or one all in? I couldn’t ask him now. If it was one all in this would be the last hand and I’d just have won fifteen of Tony’s ninety-three thousand. And could I be certain he wouldn’t call? The money was nothing to him. I wasn’t thinking clearly, I looked down to see my hand check-tapping on the felt. Control? Don’t make me laugh. My limbs were acting more decisively than me.

Tony was relentless. He fired out a bet of twenty-two thousand, and even though I knew he was at it, I’d swear he wanted me to call. I saw no choice but to do just that, and to check-call the river when (please God) he missed his hand. The dealer was turning the final card. I stared at the deck, reaching in to influence the outcome with my desperate silent pleading. Big black card . . . big black card.

And you know what, I got exactly what I asked for. No seven, no eight and no heart. The dealer peeled the deck and revealed a card as big and as black as they come: The ace of spades.

Yes!

No . . .

No, no, no, no, no!!!

Counterfeited. My hand was now two aces, two kings, and a six. Tony’s was two aces, two kings and an eight. He had the better hand. Only just but, in poker, an inch is a thousand miles.

I stared at the board, paralysed. Then I looked up at Billy Bones and his mouth widened into the kindest, most understanding and encouraging of smiles. Of course, I knew what I had to do. It was simple. Tony had the better hand, but he had no way of knowing it. If I moved all in he’d have to fold. I was only going to pick up thirty-seven of Tony’s ninety-three grand, but still, thank God I’d pulled up the extra money and could use it now to buy the pot. As clearly, as calmly and as deliberately as I could I said the two words that can never be revoked or retracted. More fateful and irreversible than ‘I do’.

‘All in.’

I waited for Tony to have his moment, to put me through the wringer and make me sweat. I stared dead ahead. And I waited. Something was wrong. He wasn’t showboating or saving face. He wasn’t folding, he was thinking. My breath was getting shallower, my heart was beating faster and I fought the strongest impulse to swallow as Tony studied me.

‘It don’t make sense, could you have an ace? Ace what? To call before the flop? To check-call flop and turn? Nah, you’d check the river to catch a bluff. A king? Nah, I know you don’t have ace-king and you don’t take all that heat with less. You never played it like a picture pair, except quad kings? But you

were scared. You still are. You don’t want a call, do you?’

This was nauseating. I knew his cards and it did me no good to know them. Knowing them was what had got me into this mess. Tony was looking straight through me and it felt as if I was the one exposed, as though it were my cards that were face up. Where’s the justice in that? But he had nothing, he could talk as long as he liked, he was never going to call.

He was still trying to put me on a hand.

‘A flush draw? No. It was five K before the flop. I know you’ve got a pair. But how big?’

Fold, you weasel. Fold and I’ll never bluff again. I’ll take up religion, become a flaming monk, so help me, just stop being a hero and throw your cards away. Should I put the clock on him? No. Don’t speak, don’t move.

Below Tony’s sharp interrogative tone I became aware of a second voice, full of syrupy concern.

‘Oh dear, mate.’

It was Billy. ‘He’s reading your soul, he’s gonna call us.’

Us?

What did he mean, ‘Oh dear’? Did he know I was bluffing too? Was I so transparent?

Still Tony talked it through. ‘Jacks you’d check. Nines, maybe? I think it’s bigger than fours. No, it felt to me like sevens, sevens or sixes. I think I’ve got to call. Whatever you’ve got, good bet.’

And with that, he pushed his chips forward, and brought my world to an end.

I didn’t move or speak for a few seconds. My mouth was dry, my throat and lungs were awash with mustard gas and my gut was boiling. Greed, fear, indecision and animosity. Four headless horsemen had ridden me over a cliff.

I spoke, faintly. ‘I had you. I had you to the end.’

I pushed my cards a few inches forward and kicked away my chair as I got slowly to my feet.

I looked around, where was he?

‘Billy Bones,’ I said. ‘Billy Bones. Ninety-five grand.’ I was yelling now. ‘I’ve just done ninety-five grand . . . to eight high. That fucking Billy Bones . . .’

‘What’s that?’ asked Tony softly. ‘Billy Bones? Funny that you should mention him. He died last week and he owed me ninety grand. They were gonna break his legs and I helped him out. Poor old Billy. I knew I’d never get it, but he swore to me. So many times he swore to me, that he’d pay me back. If it was the last thing he did.’

Jack High, Death Row

by Grub Smith

The skinny black padre, Malley, had been working on the prisoner for a long time. The closer it got to his date, the more Malley thought he could turn him around. He’d sit next to him on his bunk and talk about the scriptures, his eyes shining behind his gold-rimmed spectacles, saying how Jesus could forgive anything. Going on and on about it like a car salesman.

The prisoner let him talk. It made a change from staring at the walls. But he wasn’t looking for an easy way out from Malley, or from anyone else. He knew he was guilty, and if that meant he was going to hell, so be it. Eight years on the Row would count as pretty good practice.

He’d murdered his wife, just the way they said. Ginny. Squeezed her soft neck until she went limp. The crazy thing was, he couldn’t picture her face any more, or her smell, or even the way she wore her pretty black hair. Dating for two years, married for ten, but all the details lovers take for granted were blurred or forgotten. Only his hands retained an essence of her. He could still feel her throat, pulsing and fighting for air in the nerve ends of his fingertips, if he shut his eyes and thought about it, which he did pretty much every day.

‘Is there anything you need to tell me?’ Malley asked.

The prisoner looked around the waiting cell, at the half-eaten cheeseburger and the half-drunk strawberry shake, at the armed guards sitting a yard beyond the bars. He shrugged. Malley lowered his voice to a whisper.

‘Son, you only have a few minutes now. If you repent, the Lord is sure to forgive you. Don’t go before him with your pride intact.’

The prisoner had seen plenty of men break on the Row, stone killers caving in as Malley spun and tightened his web of words and hope around them. On their last day, they shuffled away in double irons, weakly muttering prayers. Broken by belief. The cons would discuss it the next day: ‘You won’t see me wailing like Bob did . . . who’d a thought that Davis would pussy out, he was almost holding the Warden’s hand . . .’

Staring through his own familiar bars on those melancholy occasions, the prisoner had never tried to judge the condemned men, or to catch their eyes. He’d studied Malley instead, the little padre walking backwards in front of the procession of guards and officials, reading a prayer from the black book. His voice was always the same, hushed and slow and solemn, like the words were made of iron. But under the glint of his glasses, the prisoner reckoned he could detect a hint of something else in the padre. A smirk he couldn’t hide, like he’d won a prize.

‘Well, there is maybe one thing.’

Malley leant forward, eager. ‘Tell me, son.’

‘How long do I have exactly?’

Malley checked his watch. ‘The Warden will be here in . . . just over sixteen minutes.’

The prisoner nodded calmly, then it was his turn to lean forward. He whispered into the priest’s ear, up close, seeing the whorls of flesh as a delicate purple-black.

‘Padre, are you a betting man?’

Malley twisted away, looking confused for an instant, then plain wary. But still interested; the first time the prisoner had wavered an inch in all these years. ‘I suppose that depends on the bet.’

‘I’ve got a wager for you.’ He opened the last carton on the table, and loaded his plastic fork with a slice of cheesecake. ‘All you’ve got to do is play me at one hand of poker.’

The priest shook his head. ‘You know as well as I do that Warden Swift has banned gambling for prisoners on the Row.’

‘No gambling, smoking, spitting, TV, dirty magazines and swearing. I know the list. Like things weren’t hard enough for us already.’

‘He has his methods. I can only respect them.’

‘Him? He’s a sick man and we both know it. The first day I got here, he hauled me into his office, sitting there behind his big old desk, said he’d never let me see a woman again. Never. Not even a picture in my cell. No movie stars, no centrefolds, no works of art. I wouldn’t get to read a paper that hadn’t been cut up first, case I caught a single glimpse of a female. Can you imagine what that’s been like? I haven’t even seen a photograph of my wife in eight years.’

‘You raped and killed your wife.’

‘It wasn’t rape. Not that it matters. I made love to her, then I killed her for what she’d done.’

‘The jury said different. And the Warden likes the punishment to fit the crime. It may seem cruel to you, but perhaps he’s done you a favour, keeping your mind off bad memories and temptations. Not seeing a woman, it allows you to concentrate on what matters right now, which is . . .’

‘You know I’m not even allowed a picture of the Virgin Mary.’

‘Then let’s pray to her instead. She is known to comfort us, a gentle mother to all men . . .’

The priest clenched his hands in prayer, but the prisoner put down his fork and leant back in his chair, the shackles around his ankles jarring noisily against the table leg.

‘Yeah? Well, where was she when the Warden put the cold hose on me, every day for a week last winter? When the hacks kicked me so hard I nearly lost an eye? The guy enjoys it. He’s a sadist.’

‘He believes strongly in reformation of character, and suffering is part of that. It’s a very Christian approach, in a way.’

‘Well, I’ll tell you my approach.’ The prisoner’s raised voice caused the guards to look up from their chairs, ready for trouble. He nodded at them to show he was calm, and reverted to a near-whisper. ‘You’re right about one thing, I am a proud man. So here’s the deal – one hand of stud. Five cards each. If you win, I’ll promise Jesus whatever he wants. I’ll go into that chamber singing “When the Roll is Call

ed Up Yonder”. I’ll do it on my knees if you like.’

‘It will take more than that. You’d have to feel genuine remorse.’

‘I can do that. Hell, you think I’m not sorry? I loved her.’

Malley seemed to waver.

‘Even if you don’t trust me, can you really deny me the chance?’

Malley paused. He took off his glasses and polished them on his sleeve, weighing the matter up. Finally, he spoke. ‘And if you win?’

‘Simple. You delay the Warden on the walk. Give me one extra minute on the way to the chamber. Go long on the words when you give me the last rites, tie your shoelaces, anything. I know you can do it.’

‘The execution is scheduled for 7 a.m. I can’t change that.’

‘Sure you can. The only thing the Warden fears more than upsetting the State is riling God Almighty. And who dies on time, anyway? Remember Ted Forbes from Bartram? The Jackson Lake killer? He fainted twice on the walk before they strapped him in, and then it took three squirts of gas to finish him off. They were in there more than an hour before they got it done. Or the time Doc Walker went into the chamber too early, and they had to call another medic to give him CPR? What have you got to lose?’

Malley replaced his glasses on the thin bridge of his nose. He raked his fingers back through the shallow grey hair on his scalp.

‘Here’s what I don’t understand. You’ve had eight years to wait for this day, and I’ve never met a man who seemed less worried about dying, leastways one who I’d consider sane. So why is one more minute suddenly so important now?’

The prisoner loaded another slice onto his fork, the blueberry topping smelling sweet and artificial in the stale air of the cell.

‘Padre, I’ve been a liar and a conman all my life. I’ve stolen cars, robbed stores, been in and out of jail cells since I was fifteen years old. About the only thing I ever did right was loving my wife. I never cheated on her, not once, and I wish with all my heart I hadn’t killed her. But now I can’t hardly remember what any woman on earth looks like, let alone the girl I was wed to.’

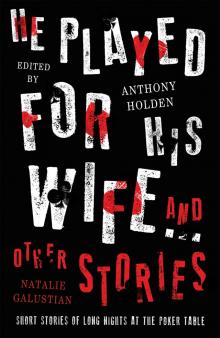

He Played for His Wife and Other Stories

He Played for His Wife and Other Stories